The New York Times and CNN are reporting this week on a scientific study on the phenomenon of flying snakes. There are at least five snake species in the world that are capable of exploiting some quirk of their physiology in order to “fly.” Certain lizards can flatten their ribs into a kind of sail, and flying squirrels “fly” from tree to tree by extending a furry membrane on each of their sides.

The new stories and study caught my eye because I met the lead scientist, Professor Jake Socha, about 20 years ago, when he was first investigating the airborne reptiles at the University of Chicago. Today, Socha is a professor at Virginia Tech, not far from where I live today.

If we can figure out how the snakes do what they do, Socha says, we have a shot at building unconventional robots that can do the same thing.

Back in the day, I drove to a field outside Chicago on a warm fall afternoon to watch snakes fly. The science magazine Discover wanted me to do an article Socha’s promising work. I remember spending the better part of that afternoon in one of three spots. I was either up on a scaffold, watching Socha release the snake from a protruding stick. Or I was on the ground, off to the side, watching the side view of the snake’s descent. Or I was just in front of the scaffold, on the ground, watching how the snake moved as he dropped down, almost at my feet.

I could have done this for hours. It was probably one of the coolest things I’d ever witnessed. The snake was a small paradise tree snake, which hailed from Asia. At first I thought, “Well, the snake’s just dropping out of the sky. No big whoop.” But no. The longer I watched, it was clear that this little dude was doing something different. A falling body would just plummet to the ground in an ungainly manner. This guy was unafraid of falling. He crawled out onto a stick, dipped down a little bit, and launched himself into the air. He wriggled through the air, and landed several feet from the presumed drop point.

We say birds and insects “fly” because they achieve lift. They can go up and down. But the lizards and squirrels I just mentioned are more often gliding. They leap from a high place, and with subtle movements direct their descent to a more desirable location—an adjacent tree—than simply hitting the ground.

I’m far from an expert on reptile motility, but that’s what the snake was doing back in Chicago all those years ago. Each time the snake launched, it seemed to suck up its belly, flatten its ribs, and turn its body into sort of an inverted U. That flattened shape allowed it to better slow its descent, and extend its linear travel path. It was not so much flying as gliding, which is just as good if nature has assigned you a lifetime of tree-dwelling. Its performance was intelligent, graceful, and amazing.

It was also, apparently, hard to photograph. At least, that’s what I was told when I got back to New York. I remember sitting in a meeting in which a renowned photographer told the magazine’s editor that he couldn’t possibly shoot the snake in the wild. It had to be in a studio with lights. He needed to set up a stationary camera, and have the snake pass directly in front of it. But he was not encouraging that the resulting shots would look good. Even if he managed to shoot a series of cool freeze-frame images, they’d be too static. How would readers of a print magazine know that the snake was flying?

It’s sort of like the problem early filmmakers faced when they started shooting movies featuring aircraft. No matter how fast a biplane was flying, aerial dogfight scenes looked pretty boring until you added a backdrop of clouds. That’s when the movie audience could appreciate the action.

Back in 2000, this editorial conversation drove me crazy. I was low on the totem pole. Just the writer. All I could pretty much do was sputter to myself. People have been looking at pictures of flying squirrels for years in nature magazines, I thought. How can you not take a picture of a freaking flying snake?

And today, as I was looking at the gorgeous footage of the flying snake in these new stories—which are here and here—all I could think was, back in 2000, I was writing for the wrong medium. What we really needed was the Internet. A good Internet, capable of running videos. And back then, a print magazine left much to be desired. And what Internet we had was shit.

The story never ran. The magazine paid for my travel to Chicago, and the nice dinner I had with Socha. I’m not even sure they paid me for the story. Because it never ran.

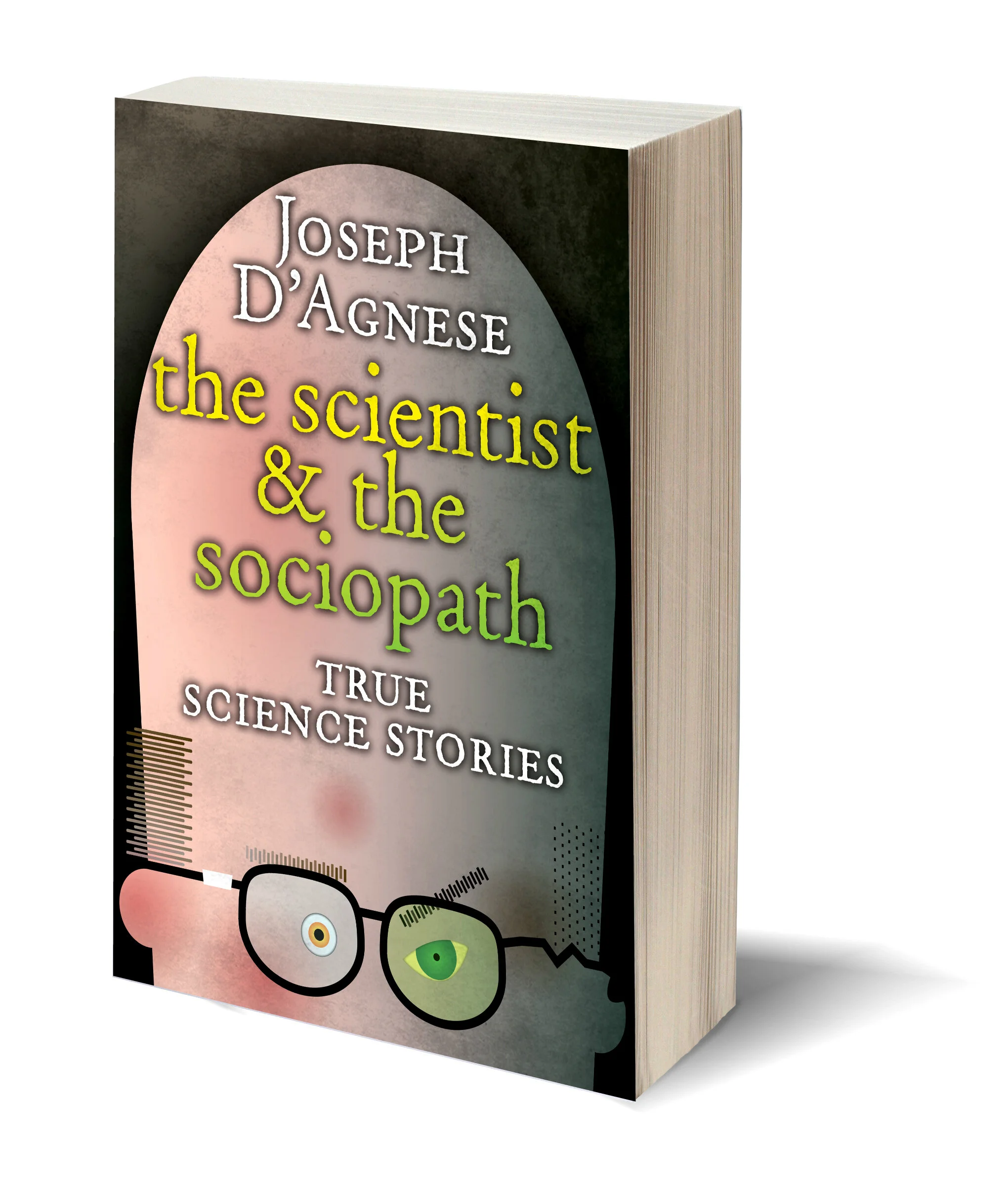

But I exacted my revenge some years later. The story finally saw the light of day in The Scientist and the Sociopath, a collection of some of my best science writing.

September 2020 update: Yes, it would be awesome if you checked out my book. But what you really should do is check out Socha’s new video on flying snakes. The snake starts flying at about the 16-minute mark in this recent video.

Professor Jake Socha, VT Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics, discusses his research studying the movement of flying snakes.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your collection of free ebooks, go here. Thanks!

***

Blue snakes at top: Trevor Cole via Unsplash