I wrote this essay back in 2005 or so, after I returned from living abroad in Italy for a year. It’s never seen the light of day until now. Looking back, I see that that short time away changed the way I interact with the nature that surrounds my home today. I’ll offer some thoughts about that at the end of the piece. But first, the essay.

I remember the first time Italy taught me a thing or two about saving money. My wife and I rented a small country apartment last winter, just an hour north of Rome. The season had been unusually cold, windy and wet, and we spent a lot of time huddling indoors in front of the radiators or else shuttling in the car between tourist sites, restaurants, and shopping. One weekend, some friends arrived just as the weather took a break from the gloom, and we all pulled on our boots and hiked up the road to check out the view.

After about 20 minutes of trudging, we met a few women outside one of the big stone houses that lined the road. Three generations greeted us, nodding as we went past. Mama, daughter, and nonna. All were well-dressed, the nonna in an elegant silk scarf. They seemed ready for Sunday dinner, with one exception: each wielded a vicious-looking hand machete. At each woman’s feet was a stack of tiny freshly cut sticks of wood. Earlier in the week, one of the men who lived here had come by with chain saw and trimmed the trees lining the family’s driveway. Now, the women were finishing the job, deftly reducing the big branches to tidy bundles of kindling.

“Buon giorno,” we nodded.

For a moment the two cultures stood staring at each other before moving on.

“Buona passeggiata,” they said. Have a good walk.

“Buon lavoro,” we said. Enjoy your work.

The scene stuck in my mind all day. Those women had been dressed to the nines, maybe fresh from church, cheeks covered with sweat, hacking away like lunatics. The house behind them was huge and handsome. One of the men who lived here, I knew, was a local judge. Surely no one who lived here needed to cut firewood to stay warm. How wonderful, we thought. Somehow they couldn’t give up on such a quaint, rural tradition. Or so we thought.

The weeks rolled by, the weather turned warm, and one day our landlord presented me with a quarterly heating bill of $500. We balked. Gently, carefully, so as not to give offense, we politely insisted that that there had to be some mistake. How could hot water, heat, and running a stove amount to $170 a month for a two-bedroom apartment? The landlord, Erminio, admitted he was puzzled too. But he dutifully ran down and got some bills from prior years. We spent a little over a half hour poring over them. It was no mistake. He’d been paying as much or more for years, during the winter months when he and his family stayed in this apartment. Natural gas is insanely expensive in Italy, especially where it must be trucked to your home and pumped into your tank, as if filling a giant car that never budges. Want to save money? Chop wood. But Erminio was a busy man with a busy career, and he had no time to chop wood. And so he grimaced and paid up. And now it was our turn.

Once I understood this underlying economic reality, everything I saw happening around me became clear. Now I understood why my neighbors were such fastidious harvesters, cutters, and organizers of wood. I understood why I could hear Signor Basili’s table saw running every night for an hour before dinner, and why he seemed obsessed with filling his woodbin. I grasped why I spied immaculately stacked woodpiles everywhere, each neater than the last. I comprehended better why, on weekends when we drove past forests, the woods themselves looked so tidy: there was hardly a spare stick of wood lying around.

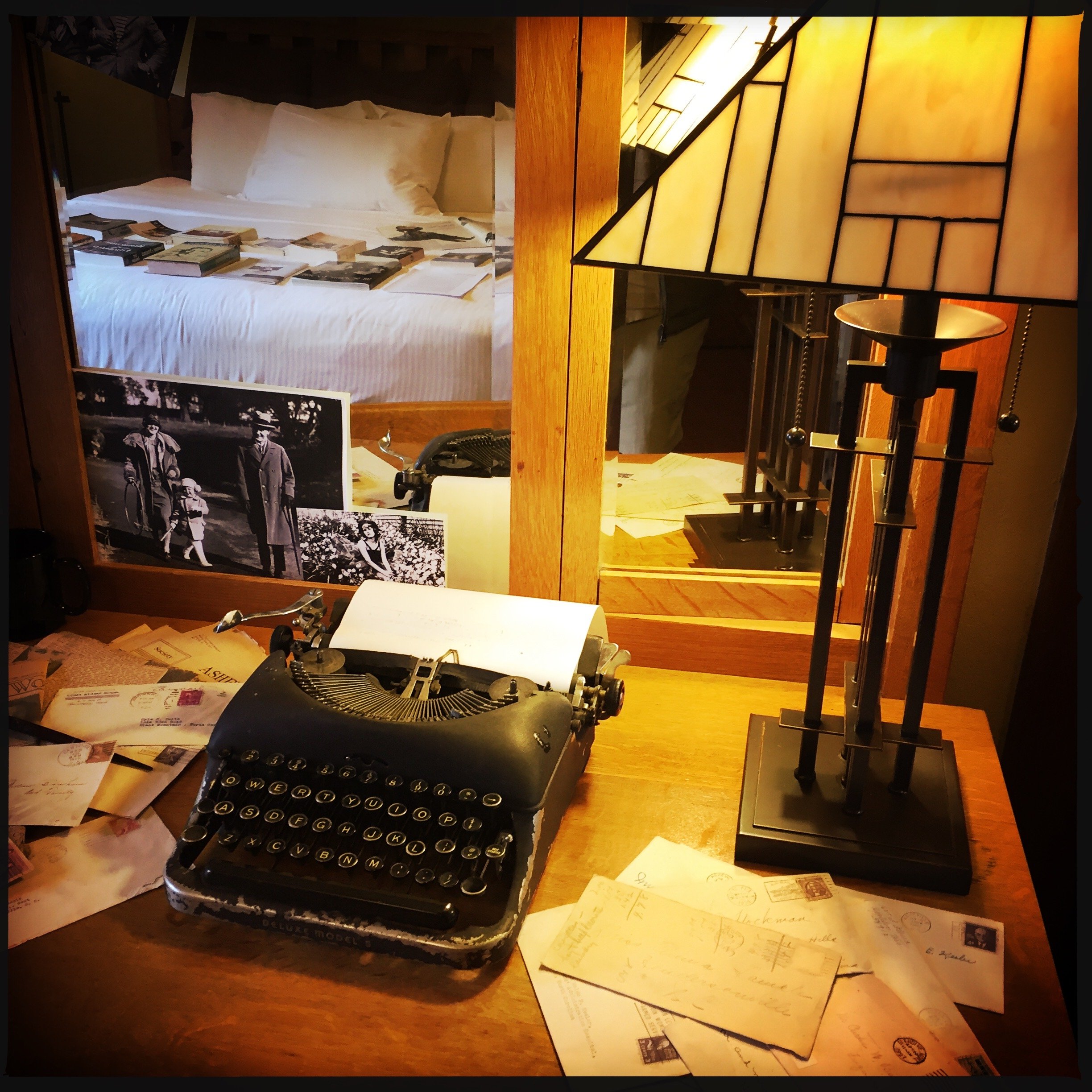

Denise making short work of an acacia tree in Italy, circa 2003.

After thunderstorms, entire embankments were picked clean like clockwork. When the state cut brush around local railroad tracks, workmen moved in with saws, buzzed the place down to the ground, and left it where it lay. In days, the locals swept in. Seniors with tiny hand saws. Weekend warriors with chainsaws, their BMWs parked by the side of the road, trunks stacked with cord wood and kindling. The occasional child following mom on the roadside, stuffing sticks into a plastic sack. Before long, the hillside was spotless, and the tiny tufts of new green sprouts signaled that the cycle was beginning anew.

What I had mistaken for a quaint, local predilection made good Euro dollars and sense.

I should say that all of these people have gas heat in their homes. Some are wealthier than the richest people you know. But they just choose not to use heat from the utility company. Granted, rural Lazio, just south of Tuscany, ain’t Alaska, but it gets cold on winter nights. Some days, when the heat wasn’t on, I saw my breath in front of my face indoors. The tips of my fingers were so cold I couldn’t type. I had been only too eager to crank up the heat, but my neighbors never fell prey to such thinking. Damned if they were going to pay when they could heat their homes or cook their food for free, all for the price of a few calories.

In this neighborhood, wood is money. Collecting and managing wood is good exercise, too, but people here would scoff if you brought that up. In winter, when the fields are empty and work slows down, my neighbors carry ladders out to each of their trees and prune them back severely. The branches go in the wood pile, and the trees’ trunks grow thicker, stronger, clubbier with each passing season, impervious to storms. Also in winter, people clip the tall reeds that grow in marshy ditches, and dry them for summer, when they use them as fence posts and tomato stakes and shade awnings. They snip the whip-like branches of the vimini, or wicker tree, soak them in water, and use them like twine to tie everything from grapevines to cucumber plants to even more bundles of wood. All summer or winter long, you can smell wood burning in the distance, meat grilling and pizzas baking over wood coals. More than any other, that delicious fragrance is the quintessential smell of Italy.

Not long after I paid for that heating bill, I returned for a visit to my hometown in New Jersey, where my parents still live. Tooling around suburbia, I saw with new eyes the place where I’d grown up. I saw untended trees everywhere; people don’t bother to intervene in their growth. Consequently, huge, fragile limbs dangled over roadways, wreaking havoc when they fell in storms. When that happened, sanitation crews came out, cut it all up, and hauled the lumber away.

Because the wood = money equation had never been drummed into their heads, my American neighbors spent money on combustible products that would have been rendered unnecessary if they simply used what grew from the earth. Free lumber went to the municipal dump, and they bought charcoal and propane tanks at the big box stores to grill their food. In fireplaces they burned synthetic logs impregnated with chemicals. Landscapers hauled away weeds. Kitchen scraps went into the trash. And gardeners bought manure, topsoil, and bags of compost for the garden. People ordered tomato cages from garden catalogs when they could use branches from the same trees which sorely needed pruning. They bought $5 bottles of dried herbs at the supermarket when a couple of perennial plants from the nursery would grow forever in their yard and give them decades of flavorful leaves for free.

Don’t get me wrong. There is nothing wrong or bad or stupid or dumb about any of this. In one culture, people had simply been trained to believe that what grew in their backyard was trash. All those branches, all those sticks, all that nature was an annual hassle that had to be collected and flung away. Powerful market forces had persuaded them if they wanted to use their fireplace, cook their food, or have a nice garden, then they had to spend money. It was a different world than the one I had seen. I wasn’t in Italy anymore. I was in America.

Almost 20 years have passed since that time away. Have we really put that much into practice? Sort of!

A fallen 90-foot pine in my backyard, circa 2022.

All our kitchen scraps and most vegetation that is not invasive goes into a compost tumbler. In fact, we’re on our fourth compost station since we started living in North Carolina. I’ve become an inveterate collector of sticks that fall from our trees, and any time I hire a tree service to take down a damaged specimen, the trunks and limbs are either ground to mulch on site, or cut into movable chunks that I use to line the trails behind my house. We burn wood in winter and fall in an outdoor fire pit. We have also cooked on that pit. (I don’t have a propane grill, but do have a wood-burning outdoor oven.) We grow a variety of herbs and flowers that are dried in a dehydrator for use off-season. We make lavender sachets to give to friends, who seem to like them. (They do keep moths from destroying your clothes!) If the woodpile (shown above), runs low, I buy cordwood from various locals who support themselves hauling and cutting wood. My house is heated by gas, so I can’t claim to have severed myself from the teat of the power company. But about half of my electricity at this point comes from the sun.

If you had asked me in the 1990s, when I was living in the New York area, if this was the life I envisioned for myself, I would have scoffed. But the signs were there. In the first apartment I ever owned in Hoboken, New Jersey, my downstairs neighbor—a Wall Street guy—had access to a yard that he never used, and allowed me to keep a small garden and tuck a compost tumbler under the apartment building’s fire escape. I grew tomatoes, lavender, and sunflowers, which his girlfriends seemed enjoy on weekends when they ventured outside.