When I meet math teachers at schools or conferences, they assume that I am a lifelong math lover since my picture book is about Leonardo of Pisa, namesake of the Fibonacci Sequence. I should come clean. Math teachers, here’s what I’ve been ashamed to confess: When I was a kid, there was no subject I feared more than math.

Meet Sarah Campbell—Another Fibonacci Author!

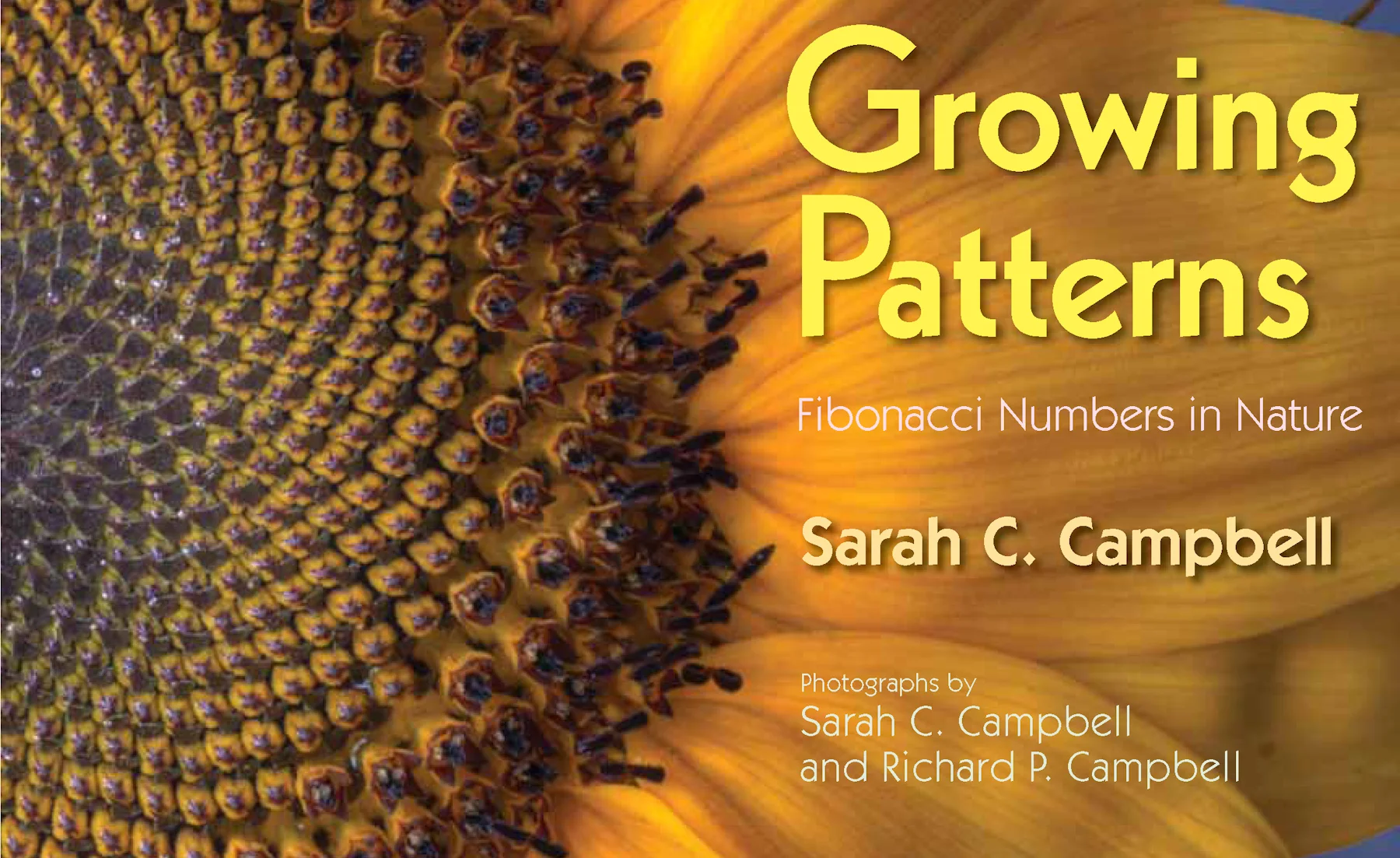

At some point all the kids in our social circle will get two books from me and my wife. One of course is Blockhead, my book about Leonardo Fibonacci. The other is Growing Patterns: Fibonacci Patterns in Nature, written by Sarah Campbell, with photos by Sarah and her husband Richard Campbell. (Boyds Mills Press).

Sarah Campbell

As it happens, my book and Sarah’s share a fun history. They were both published around the same time in early 2010, and we cross-promoted both books on our websites at the time. I did three days’ worth of posts on Sarah’s work, which I’m rescuing from my old blog, consolidating, and posting here for the first time!

Growing Patterns received great reviews when it came out. Publishers Weekly said:

“Besides being eye-catching, the photographs ought to prove invaluable for visual learners... Kids should be left with a clear understanding of the pattern and curious about its remarkable prevalence in nature.”

To which I say YES! The reason I like giving both our books to kids is that mine is illustrated, and Sarah’s employs photography. Artwork is subject to the style of the artist, but realistic photography allows kids to easily count petals on flowers, etc. Photos depict exactly how kids will encounter the various Fibonacci numbers in nature.

Here’s the full interview I conducted with Sarah back in 2010—all in one place.

Tell us about Growing Patterns, and why you are excited about it?

Growing Patterns is about a simple number pattern that has some very interesting characteristics. Growing Patterns makes Fibonacci numbers accessible to the youngest readers. It does this in two ways: by using eye-catching photographs and by connecting the number pattern to flowers and other familiar things in nature.

Your first book told the story of a tiny carnivore, the Wolfsnail. How did you make the leap from snails to Fibonacci?

It’s really not that much of a leap. I was looking for another nonfiction topic to explore that would showcase my photography (and my husband’s.) We like to take photographs with a macro lens, which means we can show snails and other tiny things in larger-than-life pictures. I love the fact that there is a snail in the Growing Patterns book; it is there as a counter-example (i.e., a spiral that doesn’t show the Fibonacci sequence.)

What attracted you to Fibonacci numbers in nature?

I found it fascinating that the seemingly wild and unique world of plants and animals follows rules that correspond to the ordered world of mathematics. I am an inveterate pattern-seeker—in music, words, images, quilts, knitting, etc.—and I wanted to share this cool pattern with kids.

In your book trailer, you say that you thought you would have to travel to exotic places to find Fibonacci numbers. But did you have to, really?

No, I didn’t. I took all the photographs at my house or in my neighborhood. I had to buy several things in the book that don’t grow locally—like the pineapple and the nautilus shell. But they weren’t hard to find.

Has anyone ever come up with a good explanation for why the pattern happens in nature?

Many different kinds of scholars, mathematicians and botanists, chief among them, have studied and continue to study this phenomenon.

How did you find what you ended up shooting? Did you look at other books for inspiration? Did you make any discoveries on your own?

I did lots of research. I looked at books and used online resources. I can’t say that I made any discoveries of Fibonacci numbers that hadn’t been catalogued before. I was convinced, however, that the sequence could be made accessible to young readers. I think that’s my contribution.

What was your favorite image to shoot?

My favorite images to shoot are the flowers; my single favorite is the peace lily. You can’t tell this from the tiny photograph in the book, but that lily was hanging in front of some crape myrtles with showy pink blossoms. The juxtaposition was lovely. What was hard was finding unique examples of the smallest flowers: flowers with one petal and two petals. In the end, we used two types of crowns of thorns to illustrate the number 2.

You are a teacher-instructor and a journalist. Can you tell us how you became a writer of children’s books?

I quit full-time journalism when my first son was born, but I knew I wanted to keep doing some kind of writing. After I had two more sons within three years, I found it hard to do journalism. At the same time, my reading habits changed radically. All of a sudden I was immersed in the world of children’s books. I decided I’d like to try my hand at writing for kids. I started by writing an article for Highlights for Children and then moved on to books.

You share the credit on this book and your last with your husband, Richard. How do you two divide the work that needs to be done to create a whole book?

I do the writing entirely by myself. We do the photography together. By this I mean that I take some of the photographs, he takes others, and we take some together. Some of the studio shots for Growing Patterns, such as the pineapple and the nautilus shell, and some of the action shots in Wolfsnail, required two sets of hands.

Can you give us a hint about what your next book will be?

I plan to write about a different tiny animal; also found around my house.

What can parents do to help kids explore Fibonacci patterns in nature?

Parents can encourage their kids to spend time outside. I also recommend giving kids bug boxes, magnifying glasses, binoculars, and cameras.

Are the walls of your house decorated with Fibonacci patterns?

Nope. My walls display lots of my sons’ artwork, photographs taken by friends and family, and some of my fabric art. Richard has a framed copy of the sunflower photograph and the Growing Patterns cover on the wall in his office at work.

How has knowing about the Fibonacci sequence affected your garden plan this year?

Our gardening hasn’t been affected yet by the Fibonacci sequence. Richard and I are working on a butterfly garden and we have raised beds for vegetables. Right now, I have seedlings of lettuce, kale, broccoli, spinach, etc. growing valiantly despite an unseasonably cold winter in Mississippi—including two snows!

Sarah later went on to write an equally charming book about fractals entitled Mysterious Patterns. The book follows in the footsteps of its predecessor, using clear photographs to illustrate this often-overlooked concept. I will often stagger the two in my gift-giving. If a child we know likes Fibonacci and Growing Patterns, the next time we see them, they get a copy of Mysterious Patterns.

You can find out more about this award-winning author on her website.

Check out Sarah’s trailer for her Fibonacci book here.

This post first appeared in slightly diffrent form on my old blog on March 1, 2010. Photo and trailer courtesy and copyright Sarah C. Campbell.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your free ebook, go here. Thanks!

Fibonacci in the Garden—Take 3

Oh Fiddleheads!

Spotted these Fiddlehead Ferns in the supermarket recently. Such a lovely example of the Fibonacci spiral. These were imported all the way from...Massachusetts. At $8.99 a pound, they are pricey, but oh so tasty with butter!

Nature's Traveling Spiral

A great question to ask kids: “What would happen if snails didn’t have spiral-shaped shells?” Remember: Spirals are nature’s way of growing compactly, of keeping a uniform, manageable shape even as the living object continues to grow. If a snail’s shell didn’t coil into a Fibonacci spiral as the snail grew, the little critter would end up dragging something resembling a long, ungainly horn after him, instead of the quite elegant dwelling it possesses!

My wife snapped this little fellow a few years ago while we were living abroad, so he is actually an Italian snail, or “chiocciola.” (Say “KEY-oh-cho-la”).

Interestingly, the Italians use the same word, chiocciola, to describe the typographical symbol at the heart of every e-mail address: @

Can you guess why?

Spirals You Carry With You

Make a fist. Ta-da! You just made a spiral. That’s right; your fingers curl up into a lovely spiral every time you clench your fist. And you carry two other spirals on either side of your head: your ears!

Fun activity for kids: Take photos of their ears and fists, print them out, and have them use a pencil to trace the spiral shape right on the photo.

Small Is Beautiful

This little guy fell out of some herbs we harvested. You can’t tell it from the photo, but he’s less than an inch long. Yet his spiral is so beautifully formed and the close-up photo on the blog shows a perfect set of ridges etched into his shell. Gorgeous! I doubt that his shape conforms to the mathematical requirements of a Fibonacci spiral. But who cares?

Green, Peppery Math

Dinner the other night called for two green peppers, which revealed Fibonacci numbers upon closer inspection. Notice: Whether you’re looking at them from the top or bottom, you can easily pick out their three- and five-lobed shapes. I have spotted four-lobed peppers, too, but they don’t strike me as being as common as the threes and fives. If I come across one, I’ll be sure to post it.

If you liked this post, check out the others in the series:

Fibonacci in the Garden, Take 1

Fibonacci in the Garden, Take 2

Learn more about my Fibonacci book for kids here.

Fibonacci in the Garden—Take 2

Just a couple of Fibonacci thoughts after a weekend in the garden…

Mystery of the Sixes

Many times I’m asked, “Why do so many flowers have six petals? Six isn’t a Fibonacci number.” Well, it’s true that six isn’t a Fibonacci number, but three is, and many times the flower you’re examining isn’t truly a six-petal flower at all. It is, instead, a three-on-three petal flower. Here’s one of my favorites—the Siberian iris. At first glance, it is a six-petal flower. But then, notice: the three center petals are different from the three outer petals. The dark outer set unfurled first, and set the stage for the lighter-colored inner set of petals. Let that be a lesson to us all. That which appears to be un-Fibonacci sometimes proves to be Fibonacci times two!

Columbine Flowers

These pretty yellow columbine flowers just popped in my garden. (I like to pretend that the little statue is of Fibonacci himself!) Looking closely, I discovered an inner set of five petals and an outer set of five petals. Fibonacci numbers circling Fibonacci numbers...

Azaleas Yes, Fibonacci No.

These gorgeous flame azaleas used to pop every spring in front of our first house in North Carolina. The old, brittle shrub wasn’t planted in the ideal spot for azaleas, and always struggled in the heat of the summer. But we loved seeing its riotous color every spring.

Azalea flowers typically have 5 petals, which is indeed a Fibonacci number. (This bottom pic of pink ones shows this clearly.) But another source tells me 5 to 7 is the the normal range. This used to make me nuts. Five to seven? Why, oh why, couldn’t it be five to eight, since eight is a Fibonacci number? The answer is, nature does whatever it wants. Statistically speaking, seven is close enough to fall into the Fibonacci range. But you’d have to count a million azalea flowers to chart the results and prove it for yourself...

If you liked this post, check out the others in the series:

Fibonacci in the Garden, Take 1

Fibonacci in the Garden, Take 3

Learn more about my Fibonacci book for kids here.

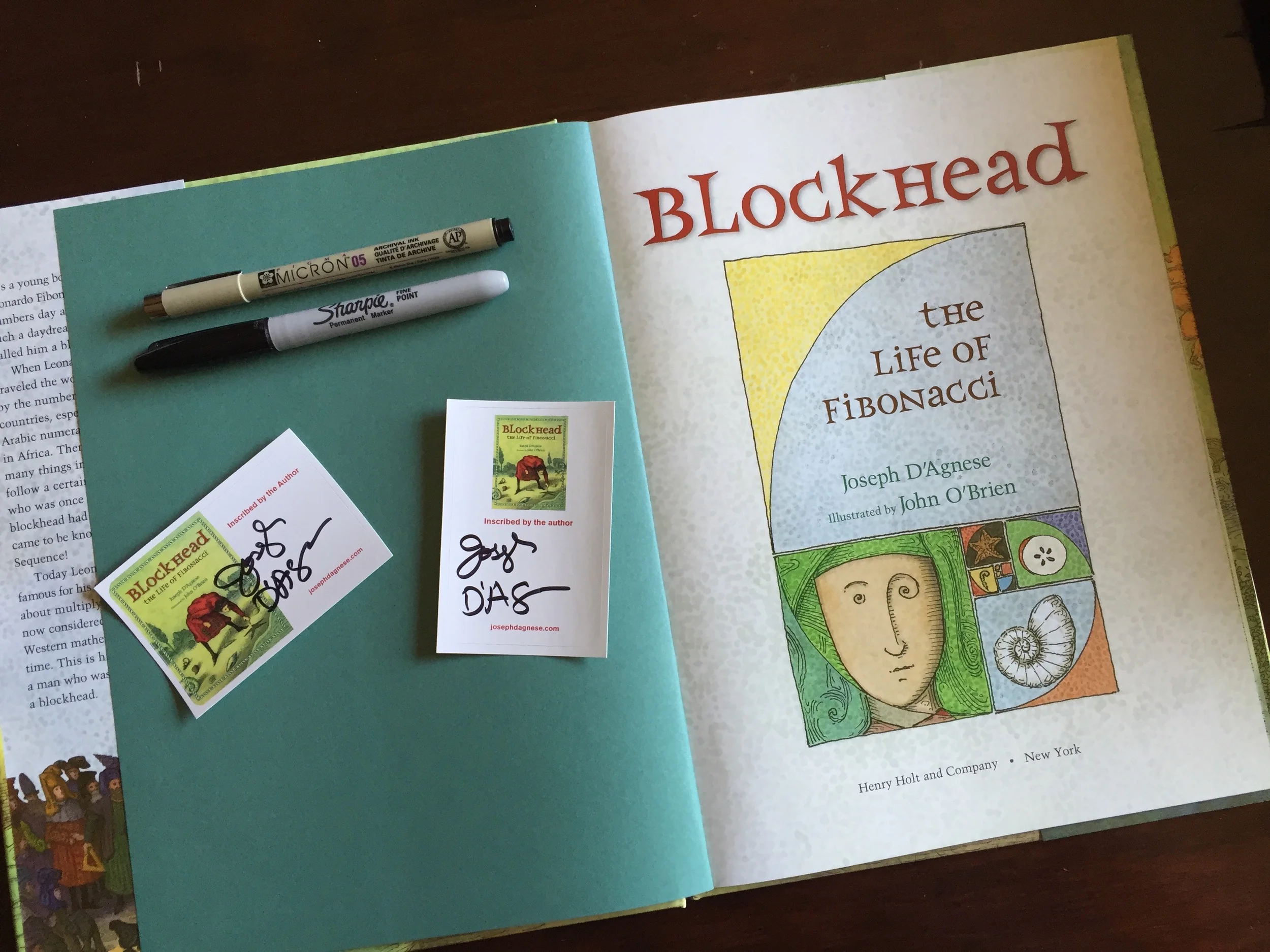

New Bookplates for My Fibonacci Book!

Two different styles of bookplate.

Many authors enjoy printing custom bookplates to give to fans of their books. I’ve never done so until now.

A friend recently returned from a trip to Tampa-St. Pete with the news that my Fibonacci book was being sold in the gift shop of the Salvador Dali Museum. I confess I had to research the venue, since I was unaware that the flamboyant surrealist had anything to do with Florida.

Turns out his work was eagerly collected by a pair of philanthropists who launched the museum in their home state of Ohio in 1971. The collection, which contains the largest grouping of Dali’s work outside Europe, moved to St. Pete in 1982. It took me a while to grasp that the gift shop was carrying my book because of its association with the so-called golden ratio, which Dali supposedly used in his work.

Shops like this are known as special-sales venues in the traditional book business. They sell books, but they’re not bookstores. And that’s usually a good thing for authors because within those four walls competition from other books is limited, and gift shop buyers have an almost moral imperative to buy something.

Since I was unlikely to get to St. Pete anytime soon to sign those books in person, I wrote the gift shop asking them if they were interested in signed bookplates. They said they could use all I could send. The book apparently does well there.

Thing was, I didn’t have any bookplates. I’d tried to design some via Vistaprint a few years ago, but their template and online designer was too complicated for my limited skills. The one on Moo.com worked really well, and I was ordering not one design, but two, in less than hour. Really, all I had to do was drop a JPG file of my book cover into the template, and add some text. Specifically, I used their Custom Rectangular Stickers. Since their website can be overwhelming, I’m providing the direct link here.

The order took a few weeks to get here. (All print jobs take forever unless you spring for rush shipping.) The resulting bookplates are pretty nice. The image of the book cover is reproduced crisply, and the paper is suitably sticky.

The only cons: I was expecting stickers about the size of those “Hi, My Name Is…” stickers, but at 3.30-by-2.17 inches, these are just slightly larger than a business card. I foolishly didn’t use a ruler to check the size before I ordered, so that’s on me, not that it would have mattered much. These are the only rectangular sized stickers Moo offers, so if I wanted to use their design engine, this size came with the territory.

Because of their size, I thought about signing my name with a Sakura Pigma Micron, which has a very fine tip. But the stickers’ waxy coating wouldn’t take the ink. So I went with a plain ol’ Sharpie instead. I think the results are pretty nice, but I prefer the horizontal design over the vertical.

Would I order these again? If I can figure out how to work with Vistaprint, probably not. I’m probably still unreasonably attached to creating a 4-by-3-inch sticker. But these designs are saved now to my Moo account, so it would be ridiculously easy to order more if the Dali Museum—or any other venue—wanted some more. And the price is $17 per 50, even less if I were to order in bulk. (The price-per-sticker drops from US$0.33 to US$0.27 if you order 400.) It’s hard to argue with the easy thing.

I may get some just to carry with my business cards. I have noticed that whenever Denise hands out bookplates to strangers, they seem genuinely excited. Bookplates drive action in a way bookmarks never can. Armed with a signed plate, you have a collectible in the making. All you need to do is buy that darn book.

If you are an author, you have one other calculation you ought to consider. As I mentioned above, the price of these bookplates can get close to a quarter. That’s not dirt-cheap by any means. Most authors are earning very little on royalties. I earn US$0.89 on every copy sold of this picture book. If I routinely gave away a 33-cent bookplate to everyone I met, it would mean that my per-book-earnings were dropping to 56 cents a book. That’s not great. But all authors like having swag to share with fans, and I think autographed bookplates are more meaningful than handing out bookmarks to anyone who breathes. And yes, under US tax law what you spend on bookplates and other promotional materials can be tax-deductible. So there’s that. The cost should not prevent you from having them made; it’s merely a consideration, and a warning not to go nuts.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your free ebook, go here.

My Fibonacci book honored with a new math #kidlit award

If you have spent any time as a child or browsed the children's section of a bookstore, you know that there are numerous awards for children's literature. The Newbery. The Caldecott. The Theodor Seuss Geisel. The Coretta Scott King. The Michael L. Printz. The Laura Ingalls Wilder. And on and on. Most are awarded each year during the American Library Association's midwinter conference. Over the years, awards have been created to honor African-American authors and illustrators, Latino/Latina creators, or to pay tribute to books that highlight the LGBT experience.

There has never been an award to specifically celebrate math-themed children's books.* Until now.

Last Friday, April 17, the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI) and the Children's Book Council (CBC) announced the first winners of their first annual Mathical Prize for math-themed children's literature. The orgs picked four winners for books published in 2014, and then picked a dozen other "Honor Books" as a way of paying tribute to books that were published in the years 2009-2013, before this new award was established.

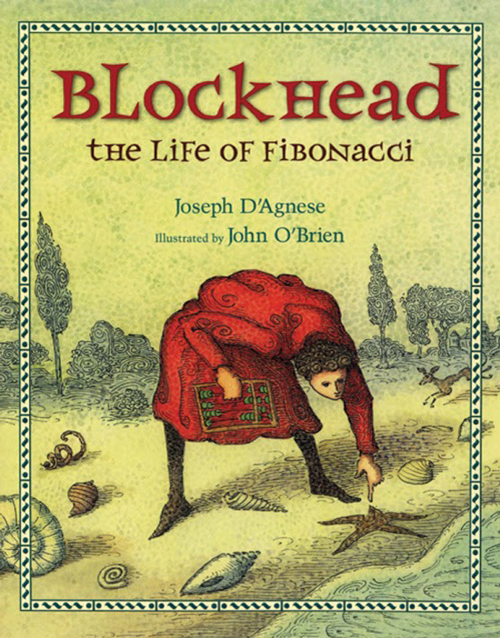

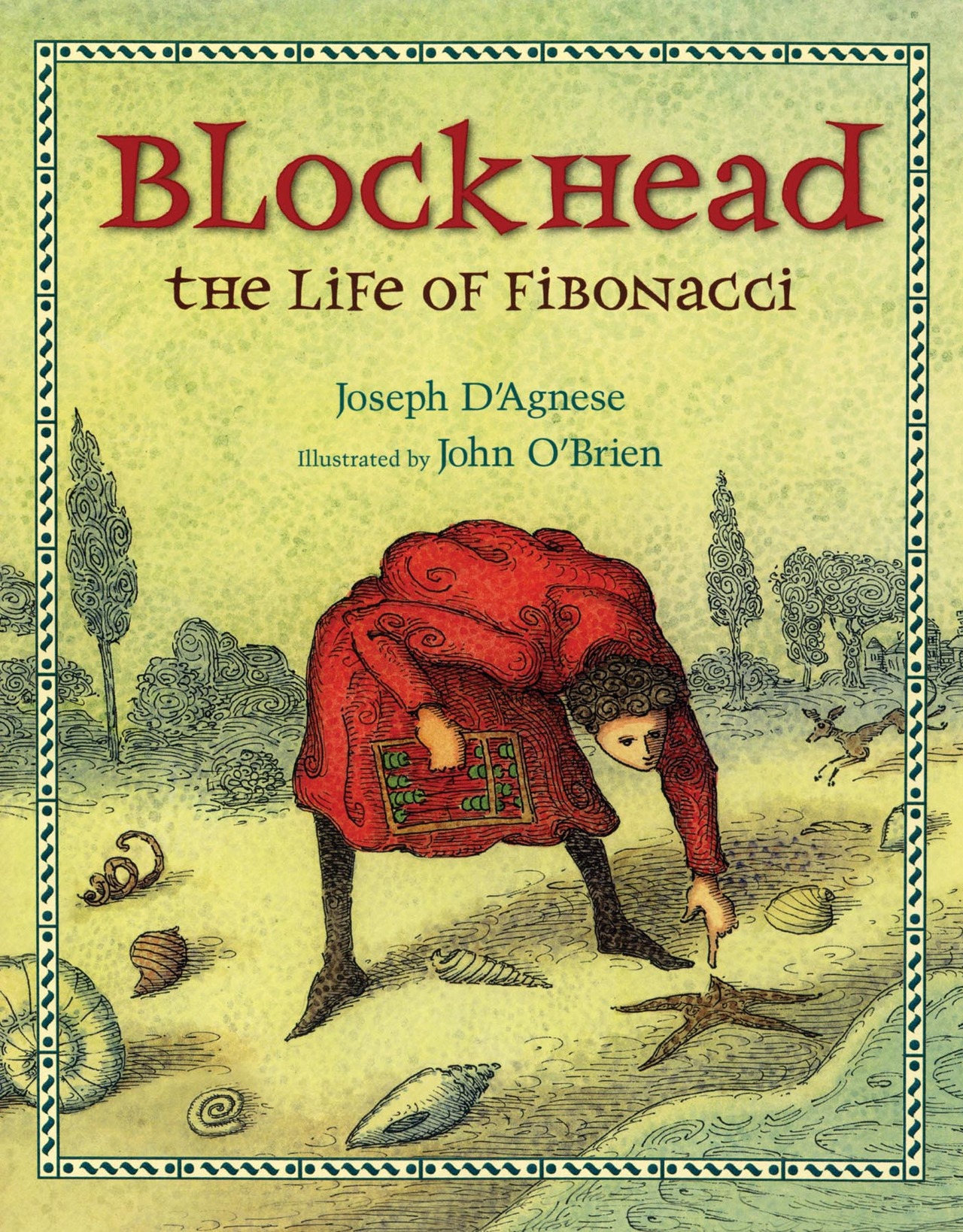

My children's book, Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci, is one of those Honor Books. Blockhead is a fable about the real-life mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci. It was published by Henry Holt in the spring of 2010. Obviously, I was stunned to get the news. In this business, you don't expect to be singled out for attention five years after the fact. But it is gratifying nonetheless.

Why math book awards? It's no secret that children learn in different ways. Children's books that touch upon math themes can inspire a child in ways that a math textbook, worksheets, or even careful instruction by a devoted teacher will not. Adults forget this, so an award that calls attention to math-themed #kidlit is not a bad way to remind them.

My thanks to these two orgs and their selection committee. My congrats to all the authors and illustrators of the 2014 Mathical Award Winners and the Honor Books.

* To be strictly accurate, in 2012 Bank Street College established the Cook Prize, which annually honors children's picture books that make perfect additions to STEM curricula. (STEM stands for science, technology, engineering and math.) The finalists for the Cook Prize are voted upon by actual kids, who choose the winner.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your free ebook, go here.

What you need to know about my book, BLOCKHEAD, about Fibonacci

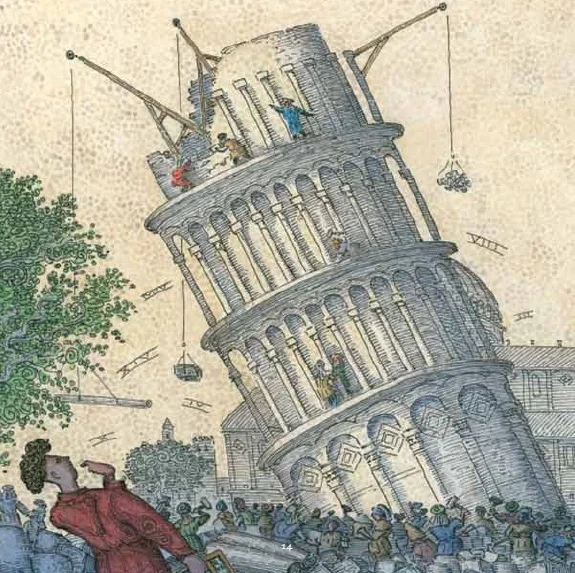

BLOCKHEAD: THE LIFE OF FIBONACCI is a charming picture book that is a fictionalized story of the real-life mathematician Leonardo of Pisa. He journeyed to Northern Africa to work in his father’s business more than 800 years ago. He was surprised to learn that the citizens of his new home didn’t use Roman numerals. He traveled the world of the Mediterranean learning all he could about the strange new Hindu-Arabic numerals. Then he wrote books to teach western Europeans how to calculate with them.

The man we now call Fibonacci is largely responsible for converting Europe from I-II-III to 1-2-3. But he’s mostly remembered for a series of numbers known as the Fibonacci Sequence, which describes how many objects thrive and flourish in nature.

PRAISE

“…the clearest explanation to date for younger readers

of the numerical sequence that is found throughout nature and still bears his name.” —BOOKLIST

“Charming and accessible…”—NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

* “The lively text includes touches of humor; Emperor Frederick called him ‘one smart cookie.’ O’Brien’s signature illustrations textured with thin lines re-create a medieval setting.” —KIRKUS REVIEWS, starred review

“Math lover or not, readers should succumb to the charms of this highly entertaining biography of medieval mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci.” —PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Fibonacci: International Supergenius

I got a box of books the other day containing foreign editions of my children’s picture book, Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci. Thus far, the book has been translated into four languages: Japanese, Korean, Spanish and Catalan.

Spanish edition.

Japanese edition.

Korean edition.

Catalan edition.

It’s always a thrill to get these foreign editions and to try to puzzle out the meaning of the words in languages I cannot read.

In this case, I was especially interested in learning how translators made sense of the English word “blockhead,” which Webster’s defines succinctly as “a stupid person.”

My use of this word in my title and story was deliberate, if a little controversial. In his day, Leonardo openly made use of his nickname, Bigollus, which people today translate as “traveler,” or “wanderer,” or even “dreamer.”

No one knows what the words really meant in the Tuscan dialect of his day, but I am persuaded that it must have had a meaning close to the modern Italian word, “bighellone,” which means “dunderhead” or “absent-minded” or “idler” or “loafer.”

While some writers on the Web persist in saying that Leonardo’s name must have been a way for his neighbors to praise this well-traveled man, I say they probably haven’t spent much time in Italy. It seems entirely in character for small-town paisani to openly mock a well-educated math genius for being an absent-minded professor type. At least, that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it.

Since I can’t read the Korean or Japanese editions, I’m setting these aside to share with a few friends who can help me out.

But since I can muddle through in Spanish and Catalan, I was please to see that these editions translate the “Blockhead” of the title as “Sonador” and “Somiador” respectively. Both words mean “dreamer.”

The title of the book in these two languages of Spain is therefore “Fibonacci: The Dreamer of Numbers.” Both are published by Barcelona’s illustrious Editorial Juventad, whom I thank profusely.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your collection of free ebooks, go here. Thanks!

Fibers & Fibonacci: The Return!

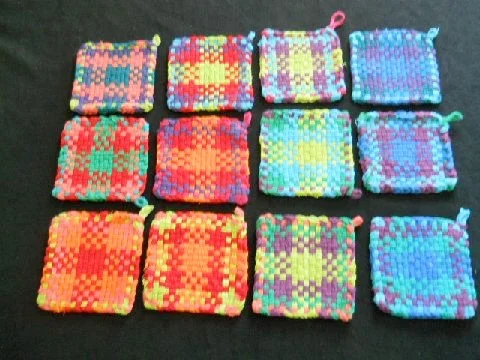

Fibonacci potholders.

Here’s more of my exchange with the leader of a weaving camp for kids. Above and below are shot of the creations the children made using the Fibonacci Sequence...

Dear Joe,

Heritage Weavers & Fiber Artists have just completed a 2nd week of Fibers Arts Camp for Kids using Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci as the focus. You would have enjoyed the closing ceremony where the campers demonstrated the activities they learned. They explained the concept of Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci, and demonstrated how they used the sequence to plan both the potholder project and the width of stripes used in weaving a book bag.

Fibonacci book bags.

I am including 2 pictures this time—more potholders (top) and a picture of the finished book bags (below). Using the sequence for proportion of the stripes seems to make any color combination pleasing to the eye.

We will look forward to meeting you at your next book signing in our area.

Ruth Howe, HWFA Camp Director

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your collection of free ebooks, go here. Thanks!

Fibers and Fibonacci

Fibonacci potholders.

I am constantly learning new uses for the Fibonacci Sequence, and ways that people in different professions use these remarkable numbers. I recently corresponded with a woman who runs a fiber arts camp for children near my home in North Carolina. Above is a shot of the creations the children made using the Sequence. Here’s what the teacher told me about it.

This is a picture of the potholders made at the Fiber Arts Camp hosted by Heritage Weavers & Fiber Artists last week at Johnson Farm in Hendersonville, NC. The Fibonacci Sequence is used with one looper of color 1, two loopers of color 2, three loopers of color 3, and five loopers of color 4, and reversed—1, 2, 3, 5, 3 ,2, 1—and then is woven in the same sequence.

As weavers, we find using the proportions of the Fibonacci Sequence are always pleasing to the eye, no matter what combination of colors are used.

Thank you for an inspiring book...

Ruth Howe, Camp Director