Fibonacci Day comes around so infrequently that I feel I must seize the day. So here are some fun facts about Leonardo…

Great Books About Fibonacci (Beside My Own)

When a kid gets hooked on a topic like number patterns or math in nature, you just want to feed that excitement because you don’t know where it is going to lead. Teachers, parents, and librarians often ask me to recommend books about Fibonacci beyond my own.

To that end, I’ve compiled what I hope is a pretty good Fibonacci bibliography. It contains books for kids, adults, and even serious mathematicians. I’m parking this list on the blog with the expectation that I’ll revise it as new books come along. The link is easily shareable if you want to shoot it to a friend or colleague…

Revisiting My 2010 Math Phobia Article

When I meet math teachers at schools or conferences, they assume that I am a lifelong math lover since my picture book is about Leonardo of Pisa, namesake of the Fibonacci Sequence. I should come clean. Math teachers, here’s what I’ve been ashamed to confess: When I was a kid, there was no subject I feared more than math.

Behind the Art of Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci

Part of the fun of our children’s book is looking for all the Fibonacci objects—bunny rabbits, pinecones, sunflowers, spirals—hidden in the artwork. Leave it to two guys from New Jersey to bring this Medieval master to life! I thought I would share the interview I had with illustrator John O'Brien back in 2010 about his sketches.

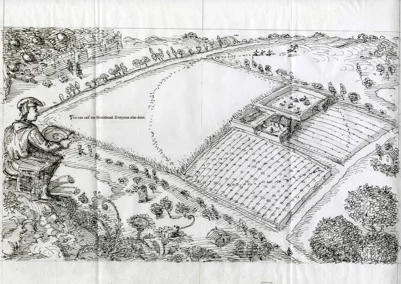

John: This is the first spread in the book. Fibonacci sits on a hill looking out over a Tuscan landscape. It's a simple scene, but it's a good example of embedding a spiral into the art before kids actually know that Fibonacci's numbers can form spirals. At the beginning, they probably aren't going to notice it. But later, when they go back through the book, they will!

Joe: You have to look closely, but it's a tiny ram or goat that's gotten loose and two farmers are chasing it across a field. The ram's tracks form a spiral. And of course, the ram has spiral-shaped horns...

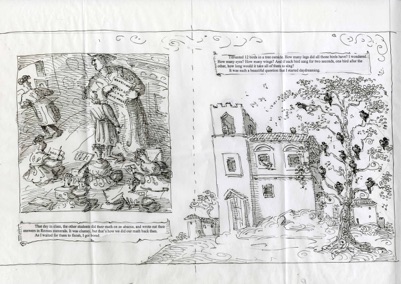

John: Spirals are hidden everywhere in this book. Sometimes they're obvious, sometimes not. If you look at the tree in this spread, you can actually see the light pencil outline of a spiral. And then I arranged the birds according to that spiral.

Joe: In the finished book, you only see the birds, not what's organizing them.

John: Well sure! Sometimes, I only do things to things for myself, to have a little fun with it!

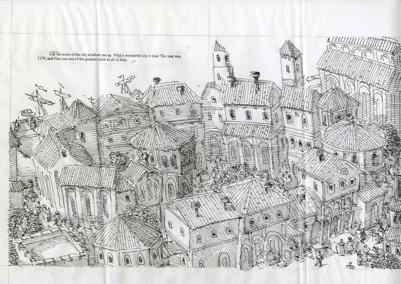

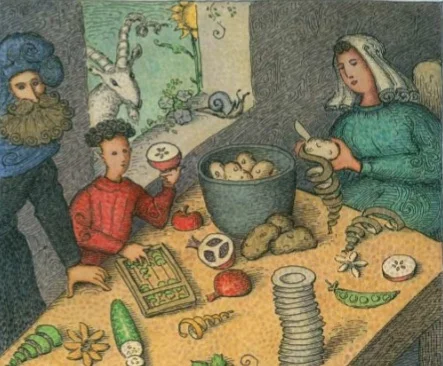

Joe: Okay, let me set this one up. This is the medieval center center of Pisa, where Fibonacci lived as a boy. He's just run away from school, and he runs out into the streets. If you look closely, you can see him in bottom right.

John: In any book, sooner or later, you have to pull back and show people the setting, give them a sense of the environment where the characters live. And if you look closely, you'll see that the buildings are arranged in a spiral shape, too.

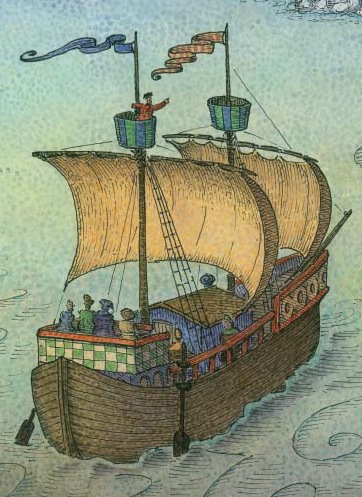

Joe: I must have looked at this a million times and never noticed that! Okay, later Fibonacci sets sail with his father for Northern Africa. I love that you hid numbers in the water beneath the ship.

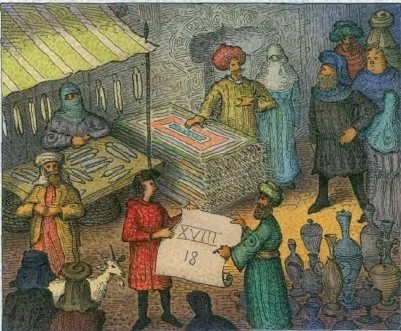

John: That was a good way to fit in the Hindu-Arabic numerals that he learns about when he's in Algeria. And you'll see that the architecture is different now. Minarets and domes. And in the marketplace I tried to put things people would have sold there. The city was famous for candles, so one of the vendors is selling candles.

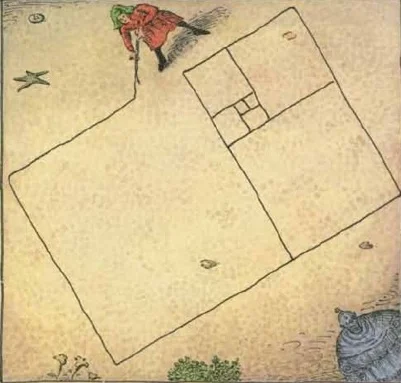

Joe: We're going to jump ahead to later in the book when Fibonacci draws a series of squares in the sand. This is the first time we explicitly show how the number pattern forms a spiral.

John: I basically did two scenes, a close-up on the left, and another from higher up when he draws the spiral. Once a kid sees that spiral, they can probably go back through the book and find all of the others hidden in the book. By the way: that's a starfish on the left. It has five arms, which is a Fibonacci number!

John O’Brien

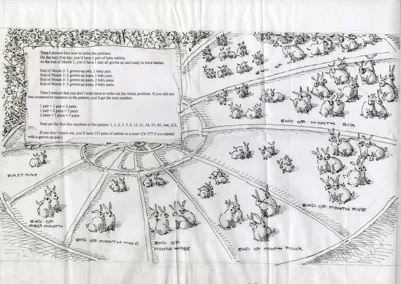

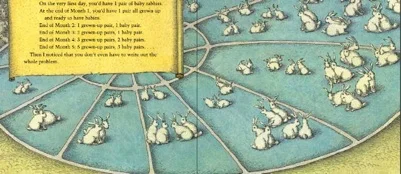

Joe: So now we come to the rabbits. A lot of people have tried to show this progression from one pair to zillions of pairs, but no one has ever drawn it this way.

John: [Laughs.] Yes, I thought it would be fun to put the rabbits inside what is basically a cut-out of a nautilus shell, which is a spiral. On the left is the first month, only 1 pair of rabbits. Then in the second month, 2 pairs. And so on.

Joe: You really only show seven months, though, John.

John: Well, sure! Otherwise I'd have to make the rabbits smaller. After a while, it's just too many rabbits!

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your collection of free ebooks, go here. Thanks!

Interview: Meet Illustrator John O'Brien

John O’Brien

When I talk to kids about my children’s picture book, Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci. I like the questions kids come up with. What’s your favorite color? Do you have pets? What’s your favorite food? But there’s one question kids always ask that deserves a more thoughtful answer. That question is: Did you draw the pictures in Blockhead? The answer, as most grown-ups have no doubt figured out, is absolutely not! The credit for the beautiful illustrations goes to a gentleman from New Jersey named John O’Brien.

I’m frankly in awe of John’s professional career. On one hand, he draws cartoons and covers for one of the world’s most distinguished magazines, The New Yorker. On the other hand, he has authored and illustrated many popular children’s books, including Did Dinosaurs Eat Pizza?, The Beach Patrol, and This Is Baseball.

At the same time, he has managed to build a life for himself that allows him to indulge in his lifelong passions. For example, at least once a week he plays with a band in downtown Philadelphia.

Though he lives in New Jersey not far from Philadelphia, he spends three months each year in Miami, Florida, and his summer months at the New Jersey Shore, where he is a lieutenant lifeguard. His love of the sea greatly inspired the beach scenes in Blockhead. Thanks to John’s illustrations, numerous librarians nominated our book for their “Mock Caldecott” awards.

John and I have only met once, at a New York signing. But we later got to hang out at one of the classic old New York pubs. I asked him to tell us about himself. Our August 2011 interview follows.

John, did you major in Illustration?

Absolutely! My school was called the Philadelphia College of Art back then but today it’s the University of the Arts. It was an artsy, fun environment with a lot of colorful teachers who taught illustration. I remember guys like Ben Eisenstadt and Al Gold, who were older gentlemen who took us under their wings. For a 19- or 20-year-old, it was an experience to hang out with these men. Ben was a collector of old illustrations, and I used to love going over his house to see what kind of images he’d picked up at flea markets over the weekend. Al was a WWII artist who drew images of things he’d witnessed during the war.

How did you become an artist? Did you like to draw and paint as a child?

Oh yes. I was probably drawing when I should have been studying. I’d have to say that half the notes I took in school were drawings.

How is the transition from New Yorker cartoons and covers to illustrating children's books?

My style is the same for both, but the books call for a more sophisticated technique. Sometimes the illustrations for children lead me to a cartoon that I later use in The New Yorker. If I do a book on Mother Goose, inevitably that leads to a couple of cartoons using Mother Goose clichés. I’m sure that Fibonacci will come out sooner or later.

Your children’s books cover so many different topics, dinosaurs, musicians, and lifeguards. Are these all interests of yours?

Not all, but a lot of them are. I’ve been a lifeguard at the Jersey Shore since I was 16 years old. The book I did about beach safety, The Beach Patrol, was very close to what we do every summer. And I play the banjo and concertina, a little bass and piano, most Thursday nights at an Irish club in Philadelphia. I also play a little Dixieland and that inspired my book on musicians.

Can you tell us how you work from sketches to finished ink work? Do you draw and paint by hand or on a computer?

Computer? No! I’m a little old-fashioned. I like playing with paper and ink and watercolors. I’m a 19th century or 20th century guy, I guess. I don’t even have a computer and I only got email last year. The work all starts with a series of pencil sketches that I do in actual size. When the sketches are approved, I draw on Strathmore Bristol Board 500 series paper, which is good for watercolors. I go over the drawings with waterproof ink. When that’s dry, I erase the pencil. Next, I apply Dr. Ph. Martin’s Hydrus watercolors, mixing the paints with a medicine dropper. That’s it. I apply layers of watercolors until I get the effect I want.

Did you enjoy working on our Fibonacci book?

The sketches are the fun part. I enjoyed playing with ideas and trying to fit in as many Fibonacci objects as possible. Once the sketches are approved, then you start the busywork. It’s like building a house from that point on. Laying it down, brick by brick, you know?

Reviewers have praised your illustrations for Blockhead: The Life Of Fibonacci, especially how you incorporated spirals and other Fibonacci objects into your scenes. Since Medieval artists often added symbolic objects to their artwork, did this inspire you?

Well, it’s a medieval subject, but I was really inspired by the art of master engravers of the 18th and 19th centuries. I still enjoy looking at their beautiful line work. The Fibonacci book just seemed to call for an element of fine art. I tried to insert as many spirals as possible because it’s important for the story. There’s a spiral on the first page, before kids even learn that Fibonacci numbers can form a spiral. But later, when they learn how the numbers are related to spirals, they will enjoy going back and finding them.

You are a man of many talents. When do you have the time to do your artwork?

Work takes a lot of time, and like most artists, I’m happy when I have the work. I think the main thing I’ve learned is that art is like music or exercise. I run four miles a day to keep in shape for the shore. It’s harder to do in your fifties than in your twenties, but you have to do it.

It’s the same with music: I pick up the banjo and play when I should be working, just to stay in shape musically. Art’s the same way. I always carry a sketchbook with me and I’m always jotting down cartoon ideas. I’d say nine out of ten ideas don’t work out. Every idea sounds great after two beers.

Also, to make more time, I get up earlier these days than I used to. I get more work done between 6 a.m. and noon than most people do in a single day. I love the early morning hours. No one’s calling you on the phone, and you can work without interruptions. Illustration isn’t a 9-to-5 thing. You have to find the time, and when you do, it’s worth it.

I used to live down in Key West, which is Hemingway’s old town. People used to wonder how he could hang out in the bars all day. They figured he wasn’t writing. But they didn’t know that he was up writing when they were still asleep. That’s the secret. Get up early. Then play.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your collection of free ebooks, go here. Thanks!

Recipe: Fibonacci Sequence Baked Beans

Back in April 2010, when my Fibonacci book was first published, one of my friends immediately sent this recipe for something he called Fibonacci Sequence Baked Beans. Every year he used to print up copies of his own personal cookbook, which he gave as gift to his friend for the holidays.

Since provenance in recipes is as important as provenance in art, I hasten to add that the recipe was sent to me by the composer Jan Powell, talented co-creator of American Tales and other works of musical theater. Jan reports that he was given the recipe by his dear friend Martha Boles, whom he reports was a math teacher in New England prior to her retirement. (The language in the recipe sounds like Jan.) Please, if you share the recipe, please remember to credit both Powell and Boles. Thank you, Ms. Boles, wherever you are...

Fibonacci Sequence Baked Beans

From composer Jan Powell, adapted from a recipe by math teacher Martha Boles.

Fibonacci Sequence: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21 … each new term in the sequence is gotten by adding the previous two. (A little math fact for those who were dying to know!)

Ingredients:

1 can (15.5 oz) kidney beans, drained

1 can (15.5 oz) butter beans, drained

2 cans (21 oz) pork and beans

3 chopped onions

5 miscellaneous ingredients:

1 tsp garlic powder

½ tsp dry mustard

¾ cup brown sugar

½ cup cider vinegar

¼ cup catsup

8 slices bacon

Directions:

“Heat oven to 350°. Sauté onion and bacon. Drain, crumble the bacon, and mix all ingredients together. Pour into casserole sprayed with cooking oil. Bake 60 to 70 minutes or until hot. (Notice: There are 5 sentences in the directions.)

“When I make these beans I frequently forgo the mathematical perfection for more flavor. For example, instead of butter beans, I use 1 can each of pinto, lima and black beans. (OK, that’s 1, 1, 1, and 3, so we’re still golden). I use the smaller cans of pork and beans.

“Also, ¼ tsp garlic powder practically eliminates one of the basic food groups. I use 8 cloves of minced garlic—hey, that number works!

“I usually sauté the bacon and onion as per the directions, but recently have discovered the fat-reducing properties of cooking bacon in the microwave (and far less mess). I just throw the onions in the casserole and bake them—more from not paying attention rather than design, but I think it works just fine. More bacon fat means a little more flavor, but who among us needs it? Enjoy!”

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your collection of free ebooks, go here. Thanks!

In Praise of Reality

These past few months, I’ve been reposting old material from my now defunct blog. This post dates back to April 2, 2010, to the week my book about Fibonacci first entered the world. The kids mentioned in the post are now in high school, but in this post they’re eternally under 10 years old.

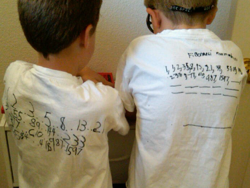

I warn you: This blog post, the fifth stop in my virtual book tour for “Blockhead: The Life of Fibonacci,” ends in something of a rant. I can’t help myself. A few weeks ago, I sent advance copies of my Fibonacci book to my two brothers to share with their children, my niece and two nephews. My niece now apparently thinks I’m a hero.

As for my nephews, well, the photos here tell the story. In one, they’re looking for Fibonacci objects on a California beach. In the other, they’re wearing Fibonacci shirts they’ve made themselves, scrawling the Fibonacci Sequence on white tees with permanent marker. On top of that, my brother reports that the boys have a new favorite snack: Fibonacci apples. This consists of ordinary apples sliced side-to-side, rather than stem-to-stem, to reveal the five-pointed star in the center of the fruit.

If you have a pulse and read even one book as a kid, you probably see something of yourself in the behavior of these kids. I know I do. When you read a book as a kid, it opens worlds. Stimulation breeds exploration. Stimulation begets investigation. Stimulation fosters imagination.

That’s why I think it’s important for parents, teachers and librarians who share Blockhead with kids to help them make the next logical leap into the world of hands-on reality. I’m going to offer just a few tips here, but I’m working on a more comprehensive list that I’ll be presenting at the NCTM math teacher’s conference later this month. [2019 Update: If you’re a teacher, librarian or parent, and want a copy of these materials, please just write via my contact page, and I’ll send you the PDF I later created from these notes.]

Kids who learn about the Fibonacci Sequence for the first time naturally want to see if the incredible number pattern really holds up in the real world. They will want to inspect plants and animals for themselves to confirm that this natural mystery really is true. Here’s what you can do to help them:

Visit a garden this spring where they can inspect flowers first-hand and count the petals to see if they display Fibonacci numbers. Consider a trip to a botanic garden near you. If you don’t have one nearby, a trip to a florist will do. Buy a few dollars worth of different flowers and let them sort them according to Fibonacci numbers. If you can’t do this, consider using Sarah Campbell’s book Growing Patterns: Fibonacci Numbers in Nature. Sarah’s crystal-clear close-up photos are the perfect substitute for the real world. Seeing is believing.

Consider planting your own Fibonacci Garden. Let kids research which plants display Fibonacci numbers, and decide which you’ll start from seed, and which will be bought live and planted. As each plant blossoms, ask kids to make a record of the numbers they see, using either a camera or pencil and paper.

If they are entranced with spirals, help them to find examples of spirals in their new garden, at the supermarket, in the woods, or at the beach. If you can’t visit a beach, visit a shop that sells seashells and buy a bag and let the kids sort them for attributes. Visit a museum or rock shop to inspect fossils displaying spirals.

If they are intrigued with the man Fibonacci, help them to research his life and times. Look at pictures of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, investigate books on the Middle Ages, and try to find Pisa and the Algerian city of Bugia (now called “Bejaia”) in an atlas. Help them plan an imaginary trip through the Mediterranean following in the footsteps of Fibonacci.

Ask them to come up with their own number patterns and challenge their friends—or you—to crack the code. See how far they can extend the Fibonacci Sequence. (Keep lots of paper handy!)

A numeral such as 1, 2, or 3 are just symbols for a larger concept of a number. The Romans used letters to express numbers. But your kids can easily come up with their own numerals. Let them try.

Have them write Fibs—Fibonacci-inspired poetry—using the number pattern as a guide. your kids might enjoy the book by Gregory K., the man who invented Fibs: The 14 Fibs of Gregory K. Remember: writing a Fib is more fun than telling a fib.

Ask them to research the lives of other men and women in the sciences and consider writing and illustrating their own picture books using Blockhead as model. Be sure that they include an activity page at the back of their books, just as we did in Blockhead.

If they are older kids, create opportunities to have them share what they’ve learned with younger kids.

For goodness’ sake, slice them up some Fibonacci apples already!

I hope you get the idea that there is no end to explorations kids can make when they are inspired to explore math’s place in the natural world.

If you’re like me, the best books you ever read as a kid spurred you to take hands-on action—sometimes good, sometimes bad—in the real world. Charlotte’s Web fostered my fascination with arachnids and the swine that love them. The book made farms seem interesting to a suburban kid. When I got older, the memory of the book’s clear, gorgeous language inspired me to seek out White’s other work. From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler forced a family expedition to the world’s greatest museum. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory inspired a somewhat messy foray into chocolate-making in my patient mother’s kitchen.

Every kid is different, and you have know idea where their enjoyment of a book will lead them. If read a book about Bob and Joe Switzer, maybe they’ll want to invent their own paints, or consider a career as a chemist. If they’d read a book about Maria Sibylla Merian, maybe they’d close the book, get off the couch, wander outside to draw pictures of bugs, and embark upon a lifelong fascination with entomology.

And don’t get me wrong. I have no problem with fantasy, either. Ask me to drive with you now through that Phantom Tollbooth, press any button in the Great Glass Elevator, or to fly with you at once to Narnia, and I’ll abandon my desk now, chair spinning. For me, these books will never lead to a dead-end cul de sac. Instead, they are screaming, eight-lane highways bound for imagination. Each time you travel down them, no matter how old you are, the road gets wider, broader, longer, richer. They take you to new and familiar places, every time.

But I freaking digress, and should stop now.

Thank you for allowing me and the old Tuscan bonehead into your life. If the old man were with us now, I’m sure he would doff his floppy cap, bow like the practiced courtier that he was, and utter a “Grazie!” as well.

Join me soon for a peek into the art of Blockhead.

Until then, keep it real.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your free ebook, go here. Thanks!

Meet Sarah Campbell—Another Fibonacci Author!

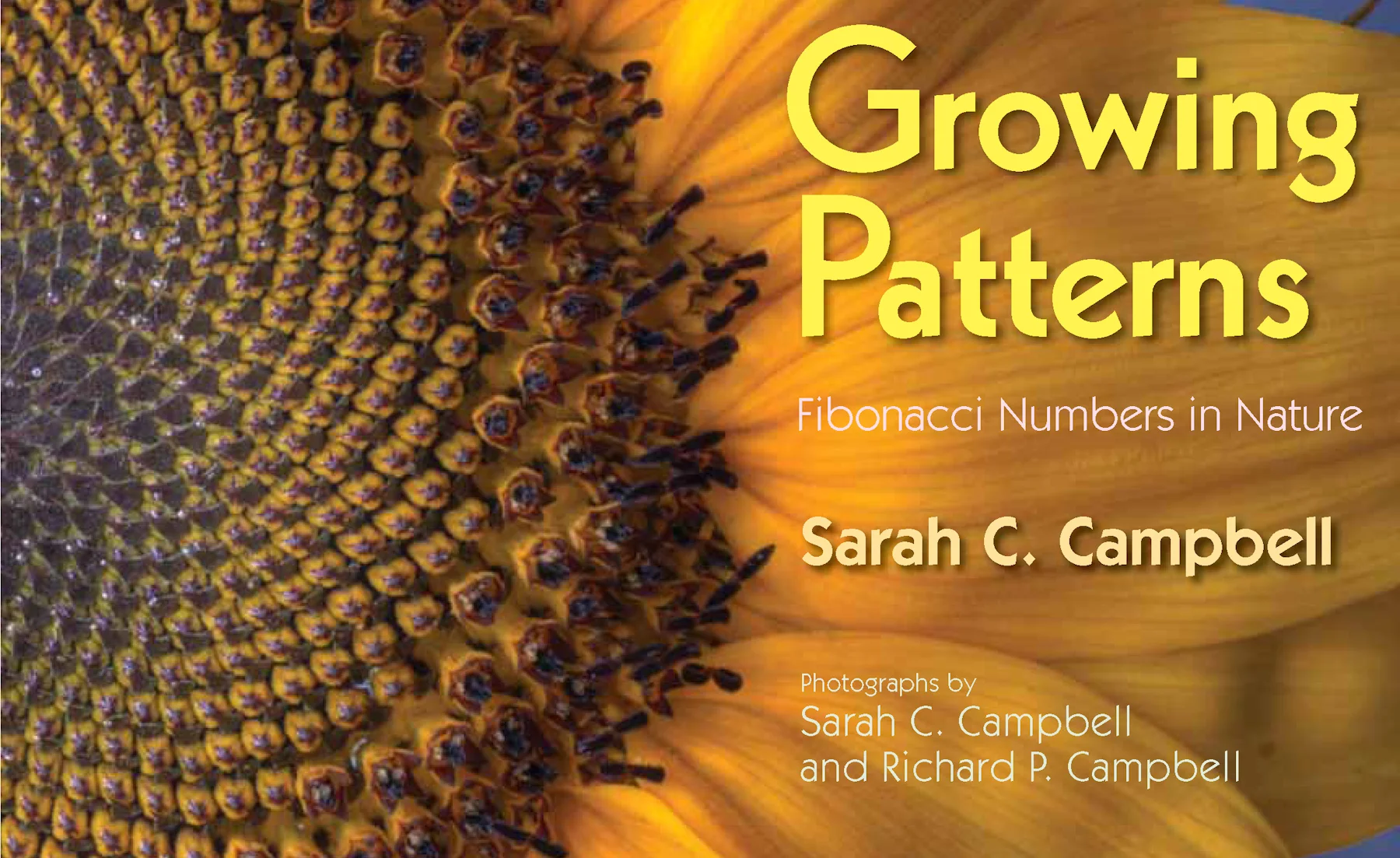

At some point all the kids in our social circle will get two books from me and my wife. One of course is Blockhead, my book about Leonardo Fibonacci. The other is Growing Patterns: Fibonacci Patterns in Nature, written by Sarah Campbell, with photos by Sarah and her husband Richard Campbell. (Boyds Mills Press).

Sarah Campbell

As it happens, my book and Sarah’s share a fun history. They were both published around the same time in early 2010, and we cross-promoted both books on our websites at the time. I did three days’ worth of posts on Sarah’s work, which I’m rescuing from my old blog, consolidating, and posting here for the first time!

Growing Patterns received great reviews when it came out. Publishers Weekly said:

“Besides being eye-catching, the photographs ought to prove invaluable for visual learners... Kids should be left with a clear understanding of the pattern and curious about its remarkable prevalence in nature.”

To which I say YES! The reason I like giving both our books to kids is that mine is illustrated, and Sarah’s employs photography. Artwork is subject to the style of the artist, but realistic photography allows kids to easily count petals on flowers, etc. Photos depict exactly how kids will encounter the various Fibonacci numbers in nature.

Here’s the full interview I conducted with Sarah back in 2010—all in one place.

Tell us about Growing Patterns, and why you are excited about it?

Growing Patterns is about a simple number pattern that has some very interesting characteristics. Growing Patterns makes Fibonacci numbers accessible to the youngest readers. It does this in two ways: by using eye-catching photographs and by connecting the number pattern to flowers and other familiar things in nature.

Your first book told the story of a tiny carnivore, the Wolfsnail. How did you make the leap from snails to Fibonacci?

It’s really not that much of a leap. I was looking for another nonfiction topic to explore that would showcase my photography (and my husband’s.) We like to take photographs with a macro lens, which means we can show snails and other tiny things in larger-than-life pictures. I love the fact that there is a snail in the Growing Patterns book; it is there as a counter-example (i.e., a spiral that doesn’t show the Fibonacci sequence.)

What attracted you to Fibonacci numbers in nature?

I found it fascinating that the seemingly wild and unique world of plants and animals follows rules that correspond to the ordered world of mathematics. I am an inveterate pattern-seeker—in music, words, images, quilts, knitting, etc.—and I wanted to share this cool pattern with kids.

In your book trailer, you say that you thought you would have to travel to exotic places to find Fibonacci numbers. But did you have to, really?

No, I didn’t. I took all the photographs at my house or in my neighborhood. I had to buy several things in the book that don’t grow locally—like the pineapple and the nautilus shell. But they weren’t hard to find.

Has anyone ever come up with a good explanation for why the pattern happens in nature?

Many different kinds of scholars, mathematicians and botanists, chief among them, have studied and continue to study this phenomenon.

How did you find what you ended up shooting? Did you look at other books for inspiration? Did you make any discoveries on your own?

I did lots of research. I looked at books and used online resources. I can’t say that I made any discoveries of Fibonacci numbers that hadn’t been catalogued before. I was convinced, however, that the sequence could be made accessible to young readers. I think that’s my contribution.

What was your favorite image to shoot?

My favorite images to shoot are the flowers; my single favorite is the peace lily. You can’t tell this from the tiny photograph in the book, but that lily was hanging in front of some crape myrtles with showy pink blossoms. The juxtaposition was lovely. What was hard was finding unique examples of the smallest flowers: flowers with one petal and two petals. In the end, we used two types of crowns of thorns to illustrate the number 2.

You are a teacher-instructor and a journalist. Can you tell us how you became a writer of children’s books?

I quit full-time journalism when my first son was born, but I knew I wanted to keep doing some kind of writing. After I had two more sons within three years, I found it hard to do journalism. At the same time, my reading habits changed radically. All of a sudden I was immersed in the world of children’s books. I decided I’d like to try my hand at writing for kids. I started by writing an article for Highlights for Children and then moved on to books.

You share the credit on this book and your last with your husband, Richard. How do you two divide the work that needs to be done to create a whole book?

I do the writing entirely by myself. We do the photography together. By this I mean that I take some of the photographs, he takes others, and we take some together. Some of the studio shots for Growing Patterns, such as the pineapple and the nautilus shell, and some of the action shots in Wolfsnail, required two sets of hands.

Can you give us a hint about what your next book will be?

I plan to write about a different tiny animal; also found around my house.

What can parents do to help kids explore Fibonacci patterns in nature?

Parents can encourage their kids to spend time outside. I also recommend giving kids bug boxes, magnifying glasses, binoculars, and cameras.

Are the walls of your house decorated with Fibonacci patterns?

Nope. My walls display lots of my sons’ artwork, photographs taken by friends and family, and some of my fabric art. Richard has a framed copy of the sunflower photograph and the Growing Patterns cover on the wall in his office at work.

How has knowing about the Fibonacci sequence affected your garden plan this year?

Our gardening hasn’t been affected yet by the Fibonacci sequence. Richard and I are working on a butterfly garden and we have raised beds for vegetables. Right now, I have seedlings of lettuce, kale, broccoli, spinach, etc. growing valiantly despite an unseasonably cold winter in Mississippi—including two snows!

Sarah later went on to write an equally charming book about fractals entitled Mysterious Patterns. The book follows in the footsteps of its predecessor, using clear photographs to illustrate this often-overlooked concept. I will often stagger the two in my gift-giving. If a child we know likes Fibonacci and Growing Patterns, the next time we see them, they get a copy of Mysterious Patterns.

You can find out more about this award-winning author on her website.

Check out Sarah’s trailer for her Fibonacci book here.

This post first appeared in slightly diffrent form on my old blog on March 1, 2010. Photo and trailer courtesy and copyright Sarah C. Campbell.

Yes, I am trying to post here more often. Thank you for noticing. If you want to sign up for my newsletter and claim your free ebook, go here. Thanks!

Fibonacci in the Garden—Take 3

Oh Fiddleheads!

Spotted these Fiddlehead Ferns in the supermarket recently. Such a lovely example of the Fibonacci spiral. These were imported all the way from...Massachusetts. At $8.99 a pound, they are pricey, but oh so tasty with butter!

Nature's Traveling Spiral

A great question to ask kids: “What would happen if snails didn’t have spiral-shaped shells?” Remember: Spirals are nature’s way of growing compactly, of keeping a uniform, manageable shape even as the living object continues to grow. If a snail’s shell didn’t coil into a Fibonacci spiral as the snail grew, the little critter would end up dragging something resembling a long, ungainly horn after him, instead of the quite elegant dwelling it possesses!

My wife snapped this little fellow a few years ago while we were living abroad, so he is actually an Italian snail, or “chiocciola.” (Say “KEY-oh-cho-la”).

Interestingly, the Italians use the same word, chiocciola, to describe the typographical symbol at the heart of every e-mail address: @

Can you guess why?

Spirals You Carry With You

Make a fist. Ta-da! You just made a spiral. That’s right; your fingers curl up into a lovely spiral every time you clench your fist. And you carry two other spirals on either side of your head: your ears!

Fun activity for kids: Take photos of their ears and fists, print them out, and have them use a pencil to trace the spiral shape right on the photo.

Small Is Beautiful

This little guy fell out of some herbs we harvested. You can’t tell it from the photo, but he’s less than an inch long. Yet his spiral is so beautifully formed and the close-up photo on the blog shows a perfect set of ridges etched into his shell. Gorgeous! I doubt that his shape conforms to the mathematical requirements of a Fibonacci spiral. But who cares?

Green, Peppery Math

Dinner the other night called for two green peppers, which revealed Fibonacci numbers upon closer inspection. Notice: Whether you’re looking at them from the top or bottom, you can easily pick out their three- and five-lobed shapes. I have spotted four-lobed peppers, too, but they don’t strike me as being as common as the threes and fives. If I come across one, I’ll be sure to post it.

If you liked this post, check out the others in the series:

Fibonacci in the Garden, Take 1

Fibonacci in the Garden, Take 2

Learn more about my Fibonacci book for kids here.

Fibonacci in the Garden—Take 2

Just a couple of Fibonacci thoughts after a weekend in the garden…

Mystery of the Sixes

Many times I’m asked, “Why do so many flowers have six petals? Six isn’t a Fibonacci number.” Well, it’s true that six isn’t a Fibonacci number, but three is, and many times the flower you’re examining isn’t truly a six-petal flower at all. It is, instead, a three-on-three petal flower. Here’s one of my favorites—the Siberian iris. At first glance, it is a six-petal flower. But then, notice: the three center petals are different from the three outer petals. The dark outer set unfurled first, and set the stage for the lighter-colored inner set of petals. Let that be a lesson to us all. That which appears to be un-Fibonacci sometimes proves to be Fibonacci times two!

Columbine Flowers

These pretty yellow columbine flowers just popped in my garden. (I like to pretend that the little statue is of Fibonacci himself!) Looking closely, I discovered an inner set of five petals and an outer set of five petals. Fibonacci numbers circling Fibonacci numbers...

Azaleas Yes, Fibonacci No.

These gorgeous flame azaleas used to pop every spring in front of our first house in North Carolina. The old, brittle shrub wasn’t planted in the ideal spot for azaleas, and always struggled in the heat of the summer. But we loved seeing its riotous color every spring.

Azalea flowers typically have 5 petals, which is indeed a Fibonacci number. (This bottom pic of pink ones shows this clearly.) But another source tells me 5 to 7 is the the normal range. This used to make me nuts. Five to seven? Why, oh why, couldn’t it be five to eight, since eight is a Fibonacci number? The answer is, nature does whatever it wants. Statistically speaking, seven is close enough to fall into the Fibonacci range. But you’d have to count a million azalea flowers to chart the results and prove it for yourself...

If you liked this post, check out the others in the series: