Thanksgiving Started as a Footnote

Backstory: Edgar Allan Poe was a frequent contributor to publications edited by Sarah Josepha Hale, who is dubbed the “Mother of Thanksgiving.”

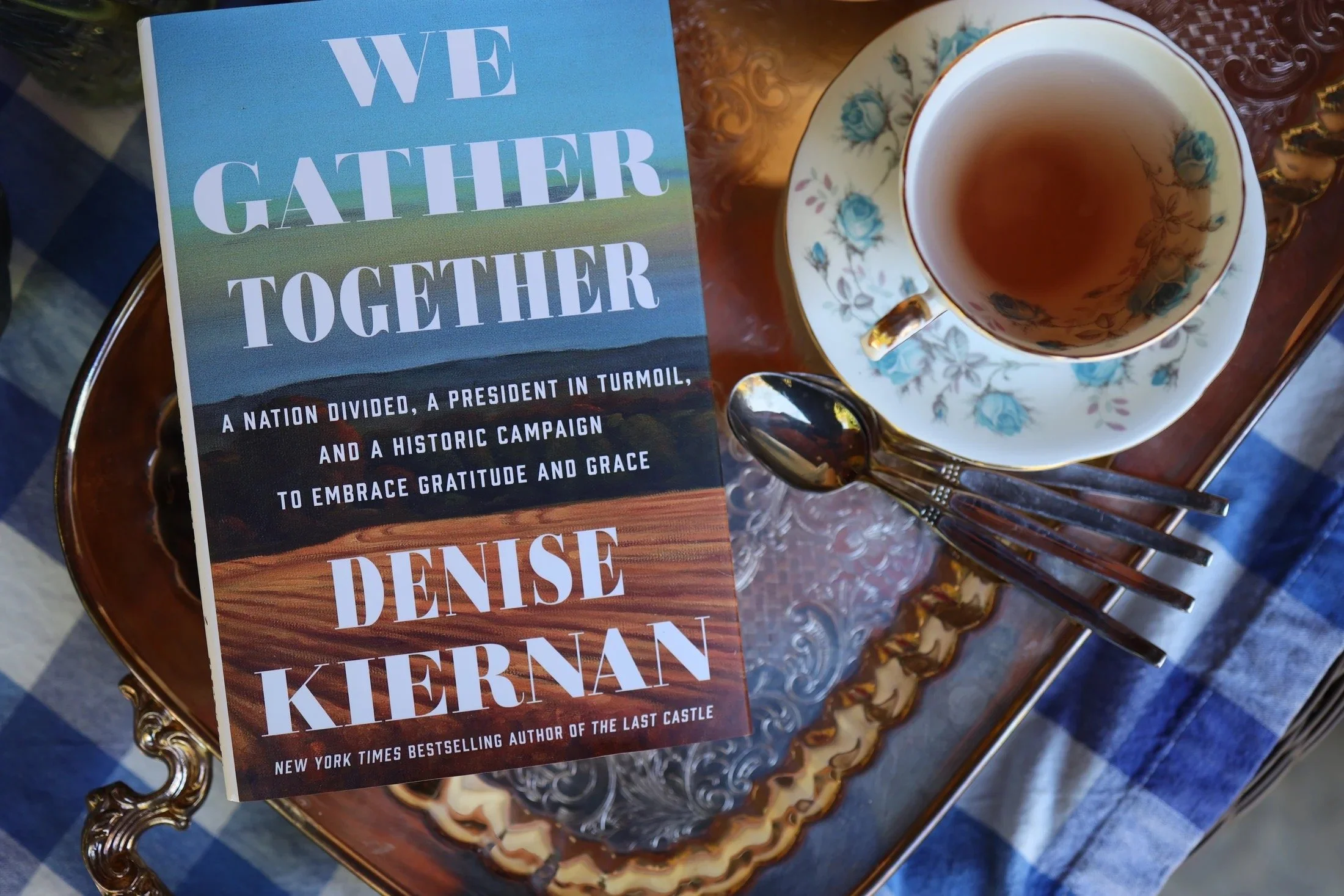

The Thanksgiving story that pops into the heads of most Americans involves a myth regarding early Massachusetts settlers called Pilgrims and Native Americans called Wampanoags. It’s a problematic story that has caused the American Thanksgiving holiday to come under fire for decades. Which is a shame, because Thanksgiving is not a bad idea for a holiday. Other nations have done well with it. Here in the USA, we foolishly linked it to a poorly understood 404-year-old historical event. My wife, New York Times bestselling author Denise Kiernan, published a book about this issue some years ago. Some of the stuff I learned during the writing of that book forms the basis for my SleuthSayers post today. The post is entitled:

Why “footnote”? That is a reference to the fact that the story of the 1621 event featuring Pilgrims and Indians was lost to history for more than 220 years. When it was finally recovered in the 19th century, a poor scholar identified it in a book as “the first Thanksgiving.” Despite abundant evidence to the contrary, the popular media of the time embraced this notion, and rammed it down the throats of Americans until myth acquired the patina of truth.

Here’s part of what I’m saying today over at SleuthSayers:

In 1844, a Boston clergyman named Alexander Young compiled a book of Pilgrim history and lore. By then, a copy of the long-lost description of the 1621 event had been rediscovered in Philadelphia. Young printed this new-to-him story of the Pilgrims and Indians, and inserted a footnote at the bottom of the page saying, in effect, Gee, I guess this was the first Thanksgiving.

He probably didn’t know of the other North American thanksgiving events that historians accept today: one in 1564 (by French Huguenots in Florida), 1565 (Spaniards; Florida), 1598 (Spaniards; Texas), 1607 (English; Maine), 1610 and 1619 (both English; Virginia). And yes, at these events, the word “thanksgiving” was noted in the record, and some of these events involved feasting with indigenous people. There are probably more. There must be. Gratitude is a universal human instinct.

The older I get, the more I understand just how much humans and Americans in particular crave myth over truth. The simpler the better. If that story quietly reinforces something we’d rather not speak aloud, all the better. When immigrants started arriving in the U.S. in droves in the late 19th century, suddenly magazine editors trotted out the first Thanksgiving myth that had been circulating since Rev. Young’s 1844 footnote, and schools passed it on, unquestioned, to children. The problem with grammar school history is that it is rarely corrected in high school or college. You reach adulthood with primitive childish notions lodged forever in your head. Ask any critical thinking American adult if they buy the Pilgrim story, and they will giggle and say no. But they’re at a loss to tell you what parts of the story are fiction.

Anyway, that’s the story in a nutshell. Go check it out.

I usually try to mention one of my books when I post here. Preferably, one that fits the topic I’m writing about. But I think Denise’s three books on the topic of Thanksgiving—written for adults, young readers, and really little kids—are a much better choice. I hope you will check them out. Those books highlight how the so-called “Mother of Thanksgiving” brought the holiday to the attention of President Abraham Lincoln during the height of the American Civil War. She was one of the preeminent magazine editors of her time. A crusader who shaped American culture. I think these books of Denise’s are a great choice for holiday reading.